Courtroom Alchemy

In Episode I, we walked the staircase of statutes that narrowed the space of lawful dissent. In Episode II, we stepped into the laboratories where “evidence” is refined, staged, and presented as certainty. Here, in Episode III, we enter the room where it all comes together. Not the ministerial office, not the laboratories of forensics, but the ordinary courtroom: the chamber where law takes a human body, a human story, and converts them into a file, a conviction, a sentence.

This is the alchemy of procedure. Alchemy here does not mean secrecy or mysticism, but transmutation: the ordinary conversion of accusation into compliance through visible, rule-bound procedure. Nothing here needs to be secret in order to be powerful. The robes, the raised bench, the dock, the scripted language, the pressure to plead, the nods, the silences, the “do you understand” rituals, all of these are visible. Yet because they are visible, they become invisible. They are treated as furniture, not as machinery.

This episode is not an attempt to prove corruption in any individual case. It is something colder and more uncomfortable. It is a study of design. Of how the room, the script, and the timetable work together to manufacture compliance, especially for the poor, the unrepresented, and the already frightened. It is an attempt to see the courtroom not as a neutral venue, but as a ritual device that converts accusation into consent.

🏛 Courtroom as Ritual Space

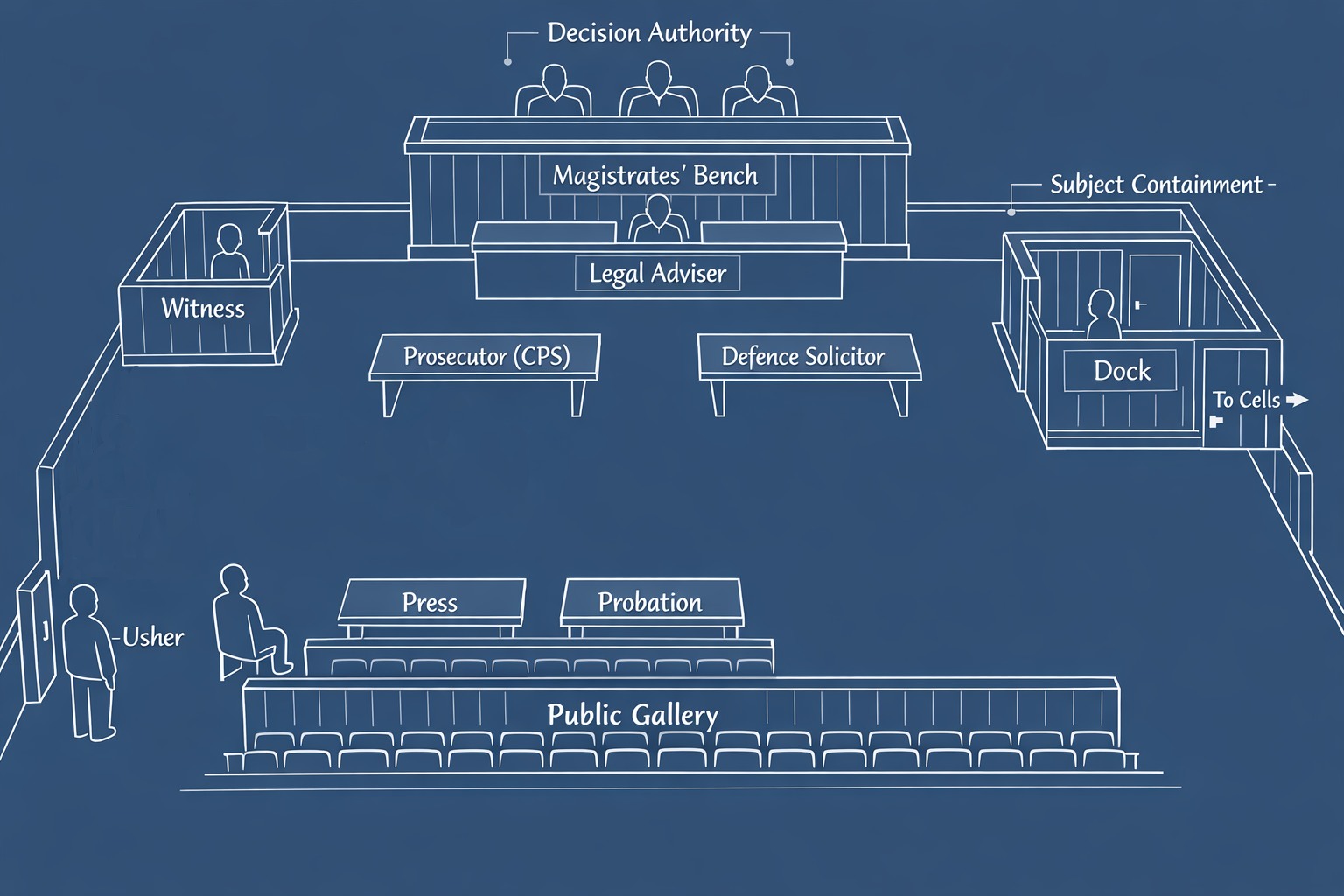

Legal textbooks rarely describe courtrooms as temples, but legal anthropology has been frank about this for years. The modern courtroom is a ritual space. The raised bench, the robed figure at its centre, the enclosed dock, the bar that separates the public from the “well” of the court, the call to “all rise”, these are not accidental arrangements of furniture. They are deliberate techniques for staging authority, channelling attention, and turning decisions into something that feels inevitable.

Architecture does part of the work. The magistrates’ or judge’s bench is elevated and central. The accused is pushed to the margins, either in a dock at the side of the room or in a chair with no table to hide behind. The public, if present, is raised at the back, close enough to witness but too far to intervene. Doors mark invisible hierarchies: one entrance for the judge, another for court staff, another from the cells. Even before anyone speaks, bodies have been sorted into roles: decision-makers above, professionals in the middle, subjects constrained to the edge.

Ritual does the rest. When the judge or magistrates enter, everyone must stand. When they sit, everyone sits. These gestures are simple, almost trivial, yet they rehearse the same message: authority arrives, authority departs, and the room breathes in time with it. A person who has just been brought from a van, placed in a cell, and led into the dock learns quickly what is expected: stand when told, sit when told, speak only when addressed.

To describe this is not to claim hidden malice on the part of individual judges or magistrates. It is to acknowledge that the room itself teaches a lesson. The person in the dock is on display. The person on the bench is shielded by height, distance, and ceremony. The courtroom functions as a device that makes inequality feel orderly, and power feel like procedure.

Stylised from typical court layouts in England and Wales. Local configurations vary.

📜 Words That Bind: “Do You Understand?”

Once everyone is in place, the alchemy moves from architecture to language. Modern criminal procedure is thick with phrases that sound like checks on fairness, but operate as triggers for the machine. Questions such as “Do you understand the charge” or “Have you had the opportunity to read these documents” appear, on their face, to test comprehension. In practice, they often test something else entirely: willingness to say “yes” so that the process can continue.

Common courtroom incantations include:

- “All rise.”

- “You are before the court.”

- “How do you plead?”

- “There is a case to answer.”

- “In the interests of justice.”

Each of these phrases carries a dual meaning. In conversational English, “do you understand” is an invitation to ask questions, to admit confusion, to slow down. In legal practice, once the answer “yes” has been given, it becomes something else: a procedural key that unlocks the next door. Comprehension is treated as established, even if the person addressed is frightened, sleep deprived, medicated, or simply overwhelmed by unfamiliar terms.

In law, these questions do not test comprehension in any meaningful sense. They operate as procedural triggers. Once answered in the affirmative, they allow the process to move forward, regardless of whether the accused truly understands the allegation, the evidence, the risks, or the long term implications of what follows.

Procedural confirmation of understanding is therefore less an inquiry into comprehension than a formal mechanism for transferring responsibility onto the individual, regardless of their capacity to meaningfully participate. The record will show that the charge was read, that the question was asked, that the answer was “yes”. The ritual of fairness has been observed, and the burden of any misunderstanding has been silently relocated onto the person in the dock.

⚖ The Tariff of Confession

Modern criminal justice openly acknowledges that early guilty pleas are rewarded. This is not hidden practice or informal pressure. It is formal policy, embedded in sentencing guidance and daily court routine.

Sentencing guidance frames these reductions as a means of sparing victims the burden of trial and preserving court resources, yet in practice the leverage falls almost entirely on defendants, who must decide under time pressure, informational imbalance, and the threat of harsher punishment whether to assert innocence or comply early.

In England and Wales, a defendant who pleads guilty at the first reasonable opportunity can receive up to a one third reduction in sentence. Delay that decision and the discount shrinks. Persist towards trial and the difference between “early confession” and “late resistance” may add years to a custodial outcome. The structure is clear: the system offers a bargain. Confess quickly, and the penalty is softened. Hold out, demand the full ritual of proof, and the system reserves the right to punish you more.

| Stage of plea | Typical discount | Practical implication |

|---|---|---|

| First hearing or earliest reasonable opportunity | Up to one third | Maximum incentive to admit guilt before full disclosure or advice. |

| Pre trial, after case progression | Up to one quarter | Pressure increases as trial date approaches, with limited time to reconsider. |

| Day of trial, after contest maintained | Up to one tenth | Resistance is formally permitted, yet materially punished. |

This is justice by throughput. The system does not need to prove guilt in most cases. It needs only to make resistance costly enough that confession appears rational.

None of this requires anyone to whisper “coerce them”. It is enough that courts are under pressure to clear backlogs, that prisons are full, that budgets are tight, and that every trial listing is a logistical headache. Within this environment, plea discounts function as a pressure valve. What is presented as a choice is experienced, especially by the poor and unrepresented, as a narrowing corridor that leads away from the risk of trial and deeper into the certainty of a recorded guilt.

🪑 LASPO’s Ghost: Unrepresented and Exposed

When the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO) removed or restricted access to publicly funded representation, it did not remove the need for legal advice. It simply changed who would go without. Defendants with money could still pay. Defendants without money could still try to navigate hearings, disclosure, and plea decisions on their own.

The withdrawal of legal aid reshaped access to justice in ways that are now routine rather than exceptional. Increasing numbers of defendants arrive at court without representation, navigating a system designed on the assumption that a lawyer will be present. Duty schemes do something, but they cannot turn ten minutes of corridor conversation into the equivalent of sustained, properly funded preparation. In practice, this often means a defendant first encounters meaningful legal advice in a corridor minutes before being asked to make a decision that will shape the rest of the case.

While legal aid restrictions were justified as a necessary cost control measure, their cumulative effect has been to normalise unrepresented defendants within processes originally designed on the assumption of professional advocacy. Court lists, guidance, and expectations have not fundamentally adjusted to the reality that the person in the dock is often reading, deciding, and speaking alone.

The alchemy here is administrative, not mystical. A line is moved in a funding document. A threshold is raised. A category is declared “out of scope”. On paper, the change is technical. In the courtroom, the change is embodied: the space at the defence table is empty; the defendant stands in the dock, turning over papers that were never written for them.

🧠 The Nodding Rite

Officially, defendants who cannot understand what is happening or cannot participate effectively have safeguards. There are tests for “fitness to plead”, for capacity, for vulnerability. In practice, these thresholds are high, and the courtroom moves quickly. Many anxious, traumatised, cognitively impaired, or mentally unwell defendants are deemed formally capable, even when they cannot follow proceedings in any meaningful way.

Fitness to plead thresholds remain narrowly defined in law, meaning many defendants who are legally “fit” nonetheless struggle cognitively, emotionally, or linguistically to engage with proceedings that move at procedural speed. The law distinguishes between those who are so impaired that the trial cannot proceed, and everyone else. The lived reality is much messier.

In that mess, ritual fills the gaps. Questions are asked. Heads nod. Boxes are ticked. The system relies heavily on the appearance of participation. A defendant who says little, nods when spoken to, and refrains from disruption is easier to process than a defendant who repeatedly says “I do not understand” or “this is not fair”. Silence and nodding become evidence, not of comprehension, but of manageability.

The nodding rite is subtle and rarely recorded. It exists in the spaces between official questions and answers: the way a defendant looks at the usher, the way a tired legal adviser offers a quiet “just say yes”, the way a magistrate or judge interprets lack of objection as consent. The transcript will contain the words “yes” and “no”. It will not contain the anxiety, the shame, the sense of being rushed through someone else’s script.

🔇 Alchemy of Silence: Administrative Consent

Where earlier sections examine what is said and how bodies respond, this section examines what happens when nothing is said at all. Much of courtroom alchemy depends not on what is said, but on what is left unsaid. Procedural rules are full of defaults. If no application is made, the case proceeds. If no objection is raised, the direction stands. If no complaint is lodged within the time limit, the decision becomes final. In administrative logic, silence is efficient. In human terms, silence is often a mixture of fear, confusion, and exhaustion.

For represented defendants, some of this burden is absorbed by counsel. For the unrepresented, the conversion of silence into consent is ruthless. A person who has never been in court, who does not know what could be asked for, who cannot afford advice, and who is frightened of saying the wrong thing, is treated in procedural terms as fully responsible for their non action. The machine moves forward, and the record reflects compliance.

This is the quietest alchemy of all. No one says “you have consented”. Instead, the file, the log, and the eventual judgment will record that nothing was opposed, nothing was requested, nothing was appealed. Administrative silence becomes indistinguishable from informed agreement.

👁 The Vanishing Oracle: Juries at the Edge

In this system of staged authority, scripted questions, plea tariffs, and administrative silence, the jury trial is an anomaly. It is the moment when twelve ordinary people are inserted into the mechanism and asked to say “guilty” or “not guilty” in their own collective voice. Unsurprisingly, it is also the most resource intensive, time consuming, and unpredictable part of the criminal process.

If the courtroom is a machine designed for efficient case disposal, the jury is the last point at which that machine must slow down and speak to the public. Most cases will never reach this point. Magistrates’ courts handle the vast majority of criminal matters. Many either end there, or are resolved by guilty plea before a Crown Court jury is ever sworn. Backlogs and listing pressures reinforce this pattern. The more clogged the system, the more attractive plea based disposal becomes. What was framed as a right to a jury trial becomes, in practice, a path that seems increasingly risky to take.

As of late 2025, proposed reform measures aimed at reducing court backlogs increasingly frame juries as an inefficiency rather than a safeguard, with suggestions to remove jury trials for lower tariff offences and certain complex cases. While presented as pragmatic responses to delay, such measures further marginalise the role of public conscience within a justice system already dominated by administrative resolution.

The courtroom blueprint makes this easy to miss. On paper, the jury box looks like just another labelled rectangle. In practice, it represents the last point at which the narrative of the State must persuade a group of ordinary citizens rather than a single professional judge or a panel of volunteers. To reduce the number of cases that reach that box is to reduce the number of times the public are invited to see and speak as an oracle of judgment, rather than as a distant audience in the gallery.

In this sense, the vanishing of juries is not merely a question of tradition. It is a question of who is permitted to pronounce the truth about another human being in the name of the community. A system that relies more and more on guilty pleas and administrative disposal is a system that increasingly speaks to itself. Critics, including criminal defence organisations, argue that such reforms misdiagnose the crisis, prioritising administrative speed over public safeguards while leaving chronic under-resourcing untouched.

🧿 Final Reflection: Refusing the Spell

Courtroom alchemy is not a matter of secret societies or hidden grimoires. It is something more mundane and more pervasive. It is the way design, language, funding, and habit combine to turn accusation into compliance. A person walks into a building that looks like every photograph of “justice” they have ever seen. They are placed in a box at the side. They are asked whether they understand. They are offered a discount if they confess early. They are told that silence will not help them, yet treated as if their silence proves consent.

To name this as ritual is not to say that law has no place. Systems for resolving conflict, addressing harm, and constraining abuse are necessary. The question is what kind of system we are willing to accept, and on whose terms. A ritual that consistently produces obedience at the expense of comprehension, speed at the expense of scrutiny, and confession at the expense of truth, is not merely a neutral tradition. It is a spell.

To see the ritual is not to reject law, but to refuse its spell: to question rehearsed consent, to defend the shrinking space of public judgment, and to insist that justice is not something performed to people, but something enacted with them. In a system that prefers nods to questions, and silence to disruption, the simple acts of asking “why” and saying “no” become small forms of spiritual and civic defiance.

🪞 Reflection Prompt

Pause and reflect before moving outward into discussion:

- At what point does procedure replace justice?

- Can consent be genuine if it is produced under fear, confusion, or pressure?

- If silence is treated as agreement, who truly has a voice in court?

- Where does moral judgement belong when legal ritual overrides understanding?

Consider these questions carefully before entering the wider conversation.

🗣️ Is justice decided, or rehearsed?

This episode examines the courtroom as a ritual system that converts law into obedience. Consider:

Can a legal process remain just if participation itself is structurally coerced?

- Is the guilty plea system compatible with meaningful consent?

- How should courts respond when defendants cannot realistically participate?

- Do efficiency and fairness necessarily conflict in criminal justice?

- What role should juries play in resisting procedural injustice?

Counter-arguments are welcome where grounded in evidence and articulated in good faith.

Continue the Conversation

All discussions are publicly readable. Posting requires an Initiate-tier account, and creating new threads is reserved for Adepts.

📖 Glossary

Legal, symbolic, and ritual terms used in SYSTEMIC: Courtroom Alchemy.

- Courtroom Ritual

- The structured sequence of language, posture, symbols, and authority through which legal outcomes are normalised and accepted, regardless of substantive justice.

- Legal Spellcraft

- The use of specialised legal language and scripted phrases to produce consent, obscure meaning, and advance procedure without ensuring comprehension.

- Procedural Consent

- The assumption that compliance with court process implies understanding and agreement, even where pressure, fear, or imbalance are present.

- Administrative Consent

- Consent inferred from silence, non-objection, or procedural compliance, rather than from informed and voluntary agreement.

- Plea Discount

- A formal sentencing reduction offered in exchange for an early guilty plea, structured in a way that incentivises confession over contest.

- Justice by Throughput

- A SYSTEMIC term describing a justice model focused on speed of case disposal rather than deliberative truth-seeking.

- False Oracle

- A system that speaks with authority and finality while substituting ritual and procedure for moral truth.

- Magistrates’ Court

- The lowest criminal court in England and Wales, handling the majority of cases and characterised by speed, limited scrutiny, and high plea dependency.

- Fitness to Plead

- A narrow legal test used to determine whether a defendant is so impaired that a trial cannot proceed, leaving many individuals who struggle cognitively, emotionally, or linguistically deemed legally capable of participation.

Resources

📑 References

- [1] Reduction in Sentence for a Guilty Plea — Sentencing Council guideline setting out formal sentence reductions for early guilty pleas, including the one-third maximum reduction at the first stage of proceedings.

- [2] Criminal Court Statistics Quarterly — Official Ministry of Justice data on court throughput, guilty plea rates, conviction outcomes, and case backlogs across magistrates’ and Crown Courts.

- [3] Barriers to Defendant Participation in Criminal Proceedings — Socio-legal analysis by Abenaa Owusu-Bempah examining how procedural design, language, and power asymmetries undermine meaningful defendant participation.

- [4] Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 — Legislation that substantially restricted access to legal aid, reshaping representation rates and procedural balance in criminal courts.

- [5] Unrepresented Defendants in the Criminal Courts — Evidence and commentary from the Magistrates’ Association on rising numbers of unrepresented defendants and the strain this places on courtroom fairness.

- [6] A Review of the Criminal Justice System Response to Vulnerable Defendants — Joint inspection assessing how courts identify and accommodate vulnerable defendants, highlighting systemic gaps in protection.

- [7] Judicial Architecture and Ritual — Legal anthropology research exploring how courtroom design, ceremony, and spatial hierarchy legitimise authority and structure obedience.

- [8] Swift and Fair Justice: Government Announces Judge-Alone Courts to Tackle Backlogs — UK government announcement (December 2025) outlining proposals for judge-alone ‘swift courts’, expanded magistrates’ sentencing powers, and jury trial limitations as measures to reduce Crown Court backlogs.

These sources are provided for verification, study and context. They represent diverse perspectives and are offered as reference points, not as doctrinal positions.